“He said that Yule is 12 days starting on the solstice, but she said that it’s 3 days starting at midwinter sometime in January!”

OK, so both are partly correct. There isn’t one single definition that has remained the same throughout history and across pagan beliefs. Most of the resources you find by searching Google give the wrong answer, so I’ll try and clear up here as simply as I can.

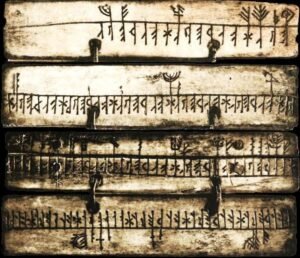

Firstly, when people give fixed (modern calendar) dates on when things like norse calendar months or midwinter etc. start, then this is misconception is based on a combination of the date of one particular event that was documented and a misunderstanding of how Julian calendars were replaced by the Gregorian calendar. The norse people used a moon-based calendar, typically 12 months to a year, with adjustments made periodically to keep the winter months in the winter and the summer months in the summer (by the insertion of a “leap month”). The details are hazy, but it seems that generally months were considered to start on the new moon, with some adjustments made around the summer and winter solstice.

There are (typically) 6 summer months (Harpa, Skerpla, Sólmánuðr, Heyannir, Tvímánuðr and Haustmánuðr), and 6 winter months (Gormánuðr, Ýlir, Mǫrsugr, Þorri, Góa and Einmánuðr). Two of these months (Ýlir and Mǫrsugr) are known as the “yule months”; Ýlir starts on the new moon towards the end of November, and runs through until the new moon at the end of December/beginning of January (or the winter solstice; accounts vary); and Mǫrsugr starts on the new moon at the end of December/beginning of January and runs through until the new moon at the end of January/beginning of February. So, in one sense, if you are celebrating “yule” at any time between end of November and beginning of February, then you’re not wrong. Evidence suggests that the yule months (especially the second) were almost month-long celebrations.

This is where the first confusion arises; the name “Ýlir” sounds like it should be related to the word “yule”, but there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of this in actual fact. The historic yule/Jól celebration (Jólablót) is said to have started in the second “yule month” is also confused with the fact that whilst Ýlir is the first yule month, it is the second winter month.

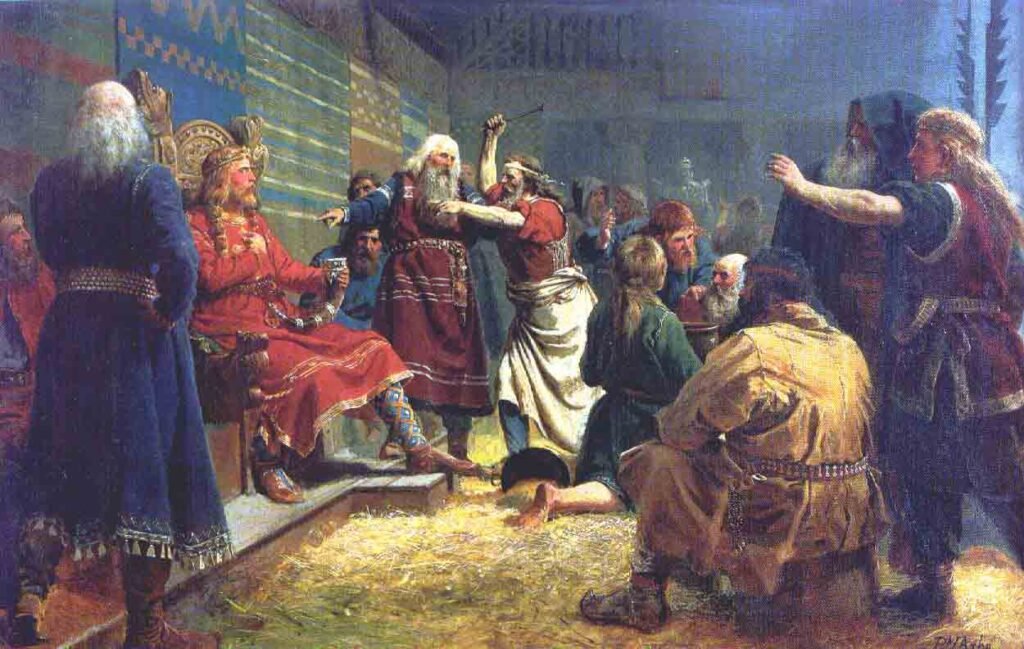

Now, not all pagans are norse pagans, and the rotation of the earth around the sun has much greater impact on our lives than the phase of the moon. So it does make a lot of sense to celebrate during the yule period on the winter solstice for many pagans. During the 10th century, during the Christianisation of Scandinavia, Christmas was also celebrated at or around the winter solstice (again, as the calendar system was changed, this was replaced with a fixed date of 25th December, but there’s reason to think that it was the winter solstice originally). And (for political reasons) the king of Norway at the time (King Hákon I) passed law to move the celebration from its original date to coincide with Christmas. So even for norse pagans, the “official” date for celebrating Jólablót has been the solstice ever since then. (This is documented in Hákonar saga góða if you want more details.)

Hann setti það í lögum að hefja jólahald þann tíma sem kristnir menn. […] En áður var jólahald hafið hökunótt. Það var miðsvetrarnótt og haldin þriggja nátta jól. Hann ætlaði svo, er hann festist í landinu og hann hefði frjálslega undir sig lagt allt land, að hafa þá fram kristniboð.

So when was Jólablót originally celebrated? In Hákonar saga góða, Snorri describes the three-day feast beginning on “midwinter night”. This agrees with Heimskringla (Magnus the Blind) which describes it as being kept “holy” for only three days. The Thietmar of Merseburg describes the blót in Lejre in his “Chronicon” (chapter 17), saying that it occured “in January, that is after we have celebrated the birth of the Lord”.

From here, we have to start piecing-together bits of evidence to work out when “midwinter night” was. The world’s leading expert (Andreas Nordberg) on the norse calendar system has written a whole book on just this subject, and the conclusion is that midwinter night is the full moon of the second yule month. (The second yule month, Mǫrsugr, being the one that starts on the first new moon after the winter solstice.)

As I said, historic accounts say that Jólablót was a 3-day celebration. So where does the “12 days” thing come from? Well, I have to admit that I couldn’t find this out for sure. It seems like this belief appeared around the same time as the Christianisation of the date. So it’s more than likely that it was also a Christian-influenced change. But who is going to argue with a reason to celebrate for 12 days instead of 3?

So what’s the conclusion? Well, the norse people had many celebrations throughout the two-month yule period in the middle of winter. Many pagans celebrate the winter solstice, which lies smack in the middle of this period, and since the mid-10th century, that includes norse pagans. And prior to that it would have been midwinter, which this winter is on 13th January 2025. So none of you are wrong. Whenever and however often you celebrate this winter, “Góð jól”.

References

Hákonar saga góða, chapter 13

Heimskringla (Magnús blindi), chapter 6

“Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning”, Andreas Nordberg

“Chronicon”, Thietmar of Merseburg

Leave a Reply